Fired Earth – Japan’s Pottery Villages and Clay

Smoke rises from a kiln in Mashiko, and the scent of clay and cedar hangs in the air. In Japan’s pottery villages, earth, fire and human hands still shape one another. Slowly, stubbornly, beautifully.

© Unsplash / Alexis Banaag

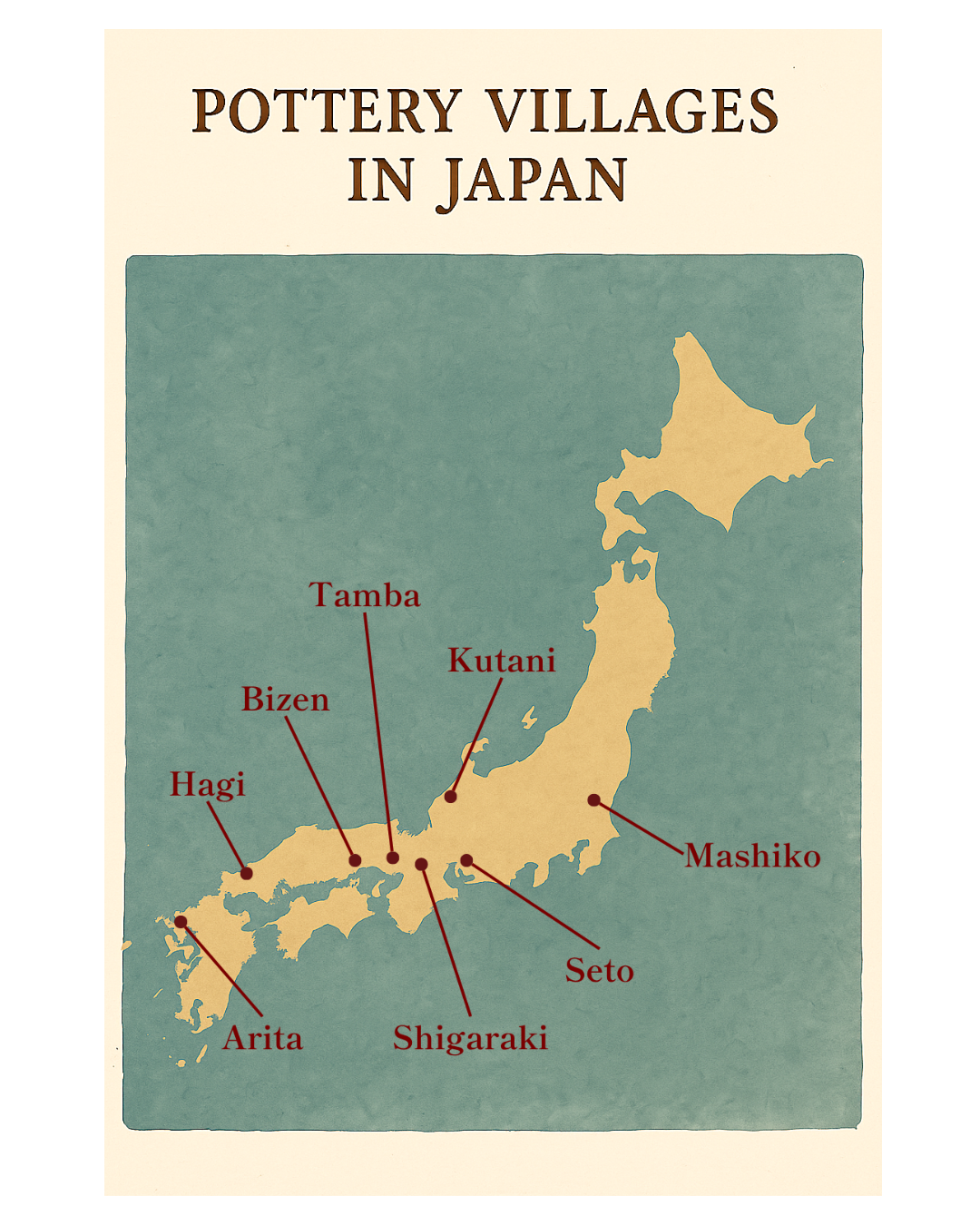

The Geography of Clay

Japanese pottery is geography made visible. Each region has its own colour, texture and temperament, determined by the soil beneath it.

Seto, south of Nagoya in Aichi Prefecture, carries perhaps the longest ceramic lineage since the 13th century. Its pale kaolin clay enabled the use of coloured glazes that, by the Edo period (1603 - 1868), had made setomono the generic word for pottery across the country. The name became so common that it blurred into identity: to make ceramics was, almost by definition, to make setomono. It still accounts for half of Japan's ceramic output!

Shigaraki, hidden in the wooded hills of Shiga Prefecture, also belongs to the “Six Ancient Kilns” of Japan. The coarse, mineral-rich clay sparkles faintly after firing, its surface marked by flame and ash rather than by brush. In the long wood-firing of anagama and noborigama kilns, molten ash drips into glassy trails known as biidoro, leaving each vessel etched with fire’s handwriting. The result is unglazed, irregular, alive.

Mashiko, north of Tōkyō in Tochigi Prefecture, tells a younger story. Its iron-rich earth first supplied Edo’s kitchens with humble jars and kettles; by the mid-nineteenth century it had become a working village of functional craft. Its transformation into an icon of modern Japanese pottery would begin not with invention, but with a return.

Other regions shaped different expressions. Arita, in Saga Prefecture on Kyūshū, discovered porcelain clay in 1616 and fired Japan’s first white ware, refined and lavishly painted. Bizen, in Okayama, kept to its reddish stoneware, unglazed and scarred by ash, favoured by tea masters for its subdued grace.

© PhotoAC / TonyG

Japan’s Pottery Villages and Their Signature Wares

益子焼 Mashiko-yaki – Mashiko ware, Tochigi Prefecture

瀬戸焼 Seto-yaki – Seto ware, Aichi Prefecture

常滑焼 Tokoname-yaki – Tokoname ware, Aichi Prefecture

信楽焼 Shigaraki-yaki – Shigaraki ware, Shiga Prefecture

丹波立杭焼 Tamba-Tachikui-yaki – Tamba ware, Hyōgo Prefecture

備前焼 Bizen-yaki – Bizen ware, Okayama Prefecture

九谷焼 Kutani-yaki – Kutani ware, Ishikawa Prefecture

萩焼 Hagi-yaki – Hagi ware, Yamaguchi Prefecture

有田焼 Arita-yaki – Arita porcelain, Saga Prefecture

The Folk Craft Legacy

In 1924 the potter Hamada Shōji returned from England, where he had studied with Bernard Leach, and travelled north to Mashiko. He could have stayed in Tōkyō’s art world; instead he built a kiln in the countryside, choosing proximity to earth over prestige. At the same time, the thinker Yanagi Sōetsu was shaping a philosophy that would give this decision its name. 民芸 mingei — the “art of the people” — honoured the anonymous maker, the everyday bowl, the quiet perfection of usefulness. Beauty, Yanagi argued, was not an aesthetic of rarity but of sincerity.

What Hamada revived in Mashiko was not nostalgia but method. He rebuilt the discipline of craft from the ground up: clay from nearby hills, glazes mixed by instinct, firing judged by flame-colour rather than thermometer. Each decision reconnected maker and material, rejecting the distance between art and work. To knead, to throw, to fire. Hamada used only local materials, mixed his own glazes, made his own brushes, and stopped signing his work. “Why would you claim as your own,” Yanagi asked, “what passes through forces greater than one person’s hands?” The gesture changed everything. Mashiko became a pilgrimage site for craftsmen who wanted to live by hand and mind alike. The mingei movement spread from Japan to the West, influencing generations of potters and designers who saw in its humility a form of resistance to industrial speed. Not feeding an individual artistic ego, but building community.

Hamada was named a Living National Treasure in 1955, but the honour mattered less than the continuity it represented: a way of working where care replaced ego and repetition became meaning. A bowl, used daily, could be as eloquent as a painting.

© Unsplash / Tyler Zhang

The Makers of Today

Years later, Mashiko remains a village of makers. More than 250 kilns and 300 studios, some family-run for generations, others opened by newcomers from abroad. In Japan, craftsmen usually inherit their craft, but in Mashiko, anyone can learn pottery. In a workshop, the day begins with water. Clay is kneaded until its air pockets disappear. A slow, rhythmic folding called kiku neri, “chrysanthemum kneading.” At the wheel, the potter centres the lump with steady pressure; a misaligned heartbeat will tilt the whole form. Once shaped, the vessel must dry for days before it can be trimmed, glazed, and finally fired. Each step is both routine and meditation, repetition without boredom.

Twice a year, during the Mashiko Pottery Fair, tents line the streets and hundreds of thousands of visitors come not to browse souvenirs but to choose pieces that feel alive in the hand. The Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art hosts international residencies, bringing together Japanese and foreign artists in shared studios. The goal is not fusion but dialogue: different traditions meeting at the wheel, exchanging techniques, then parting with renewed respect for material and process.

In Shigaraki, the great anagama kilns still glow. Their stokers feed them for days, reading the colour of flame to judge heat, trusting intuition more than instruments. The method remains unchanged because the physics of wood and air will not modernise; each firing is a conversation between flame and patience. Elsewhere, in Bizen and Seto, new generations are reimagining old forms, combining ancient firing with contemporary design. Some exhibit abroad, others work quietly for local markets. The pace is slow, but the confidence is steady: tradition is not a relic but a living argument about what still matters.

穴窯 Anagama kilns are traditional, single-chamber, wood-fired kilns built into a hillside. The name literally means “cave kiln” (ana = hole, gama = kiln). They date back over a thousand years, introduced from China and Korea, and remain central to Japan’s oldest pottery traditions such as Shigaraki and Bizen. Unlike modern gas or electric kilns, anagama kilns are fired continuously for several days or even weeks. Potters feed them with wood around the clock, guiding temperature and airflow by intuition. © PhotoAC / y-kuma

Clay as Continuity

Pottery in Japan carries a philosophy of time. The concept of wabi-sabi — beauty found in imperfection — and the practice of kintsugi — repairing with gold — are not metaphors here; they are working principles. A cracked bowl is not discarded but mended, the fracture traced in lacquer and powdered metal. The gleaming line is not concealment but testimony: a record of use, of loss, of care. The object becomes more itself through damage. This acceptance of impermanence runs through Japan’s crafts. A vessel made to last, to age, to be repaired, expresses faith in continuity rather than permanence. It is a small defiance against disposability. Everywhere young potters still centre their clay knowing that many pieces will fail, crack, or never sell. Yet they continue, because the act of making is the meaning. The wheel turns, the clay remembers, the kiln decides. Next time bring home a piece that has the quiet confidence of outliving your whole family!