Back to Abbeyglen: A Meeting with Ireland’s Past

In the rugged hills of Connemara stands an ancient castle that once offered refuge to Ireland’s forgotten children. Today, its weathered walls warmly welcome travellers from every corner of the globe. When I met a man who had grown up there as an orphan, the country’s complex and often painful past suddenly felt vividly close and deeply personal.

The first thing you see when you land at Ireland West Airport Knock is a sign that feels both modest and miraculous. There’s no city skyline, no chaos of arrivals. Just wind, hills, and a runway built on a dream. Local legend says the place exists thanks to one priest with a vision – or a stubborn streak. Monsignor James Horan wanted an airport in the middle of nowhere. Dublin said no, experts said impossible. Horan smiled, prayed, and built it anyway. The airport opened in 1986, against reason and weather alike. His spirit lives on in every departing flight and every raised eyebrow. Be delusional, I thought. The phrase had been circling my mind for months – a reminder to believe in unreasonable dreams. Maybe it’s a fitting motto for Ireland itself: a country built on poetry, contradictions, and people who never stop believing in something improbable. As I walked to my rental car, I thought of Horan’s defiance. Be delusional, I told myself. It felt like the only sensible advice for a three-week solo trip along Ireland’s west coast.

Arrival in Connemara

My first stop was Clifden, the unofficial capital of Connemara region, in County Galway. The road wound through a landscape that seemed permanently half-dreaming. Green and grey, soft light on stone walls, clouds moving like thoughts you couldn’t quite catch. Abbeyglen Castle appeared on a hill above the town, its turrets peeking through trees. From a distance it looked like a fairytale, up close like a house that had seen too much life to still believe in fairytales.

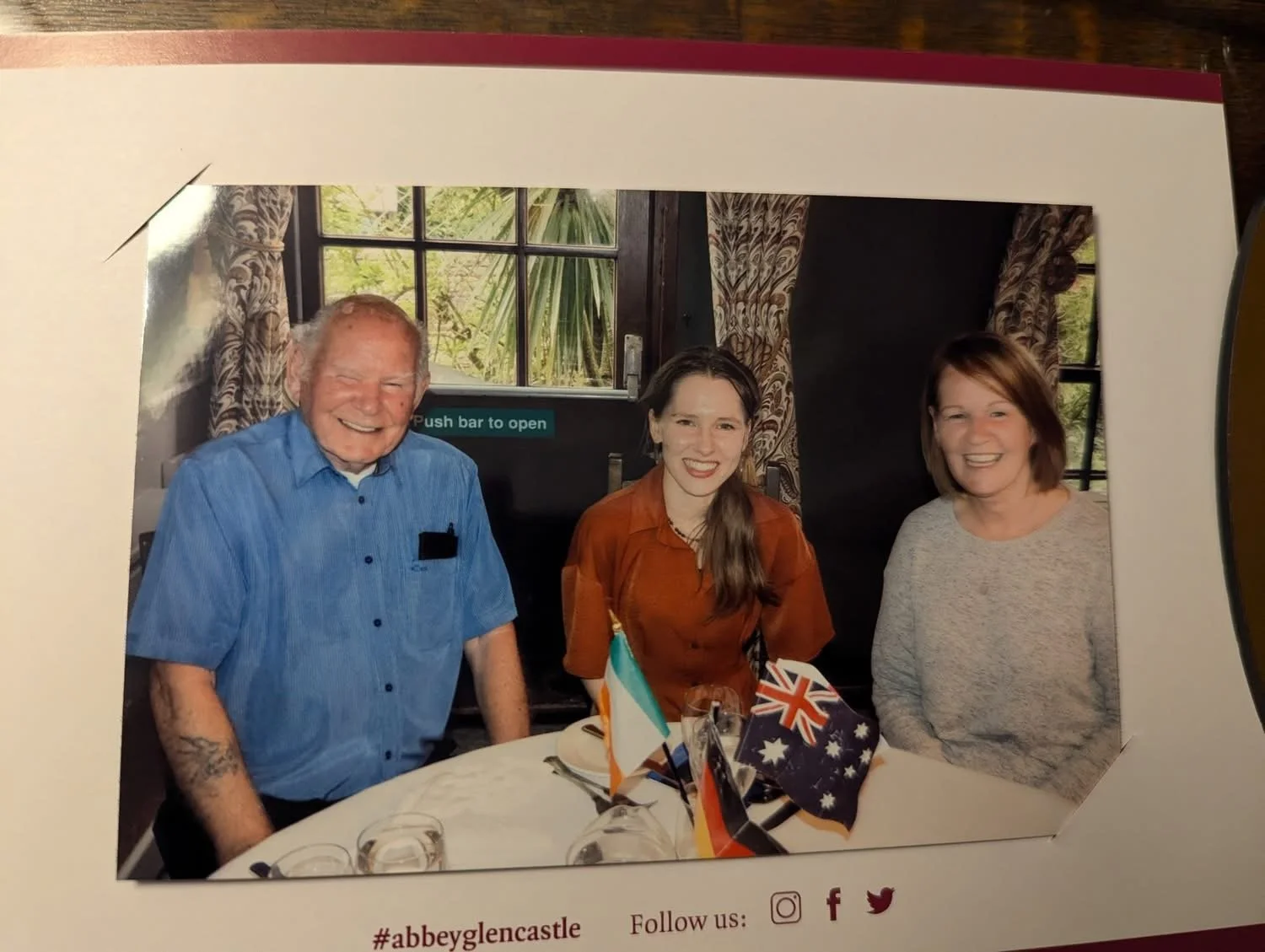

That evening, guests were gathered for a small champagne reception by the fireplace. The kind of event that feels slightly too elegant for the Irish weather. Glasses clinked, laughter drifted between wood panels, someone played the piano as if testing the patience of the keys. It was there I met an older man and his daughter. He had that calm self-possession of someone who had lived through many chapters. She had come from Australia, where she restores and sells houses. They’d decided to travel together for a few weeks, revisiting places from his past. They invited me (poor little solo traveler) to join dinner and, later, a few glasses of wine by the fire. It was easy company. The kind that forms naturally when you’re far from home and slightly adrift.

A House with Many Lives

Abbeyglen’s walls have absorbed more than one kind of story. The building was first constructed in 1832 by John d’Arcy, the founder of Clifden. It was originally called Glenowen House and later gifted to the local parish. By the 1850s, it had taken on a different role: an orphanage and training home run by the Irish Church Mission Society. Here, Protestant boys and girls — often those who didn’t fit into Catholic Ireland — were raised and educated until around 1955. When the home closed, the building fell into disrepair; for a time, it was used to shelter livestock rather than children. In the 1960s, new owners began restoring it, eventually transforming it into a hotel. Since 1969, the Hughes family has run Abbeyglen Castle as a place of hospitality and nostalgia, perched between the Twelve Bens mountains and the Atlantic. It’s a beautiful kind of irony — a building once defined by exclusion now welcoming guests from all over the world.

Echoes in the Walls

Only later that evening did I learn that the man I’d met had once lived here as a boy. It wasn’t a dramatic revelation, more a quiet fact that changed the air in the room. He had been sent to Abbeyglen like many children whose fates were decided by faith and circumstance. Because he wasn’t Catholic, no Irish family took him in. Eventually, he was sent to Britain, where he built a different kind of life. Solid, respectable, not so far from the west of Ireland. Now, decades later, he had returned. He wanted to show his daughter where he came from.

I watched them together. Her curiosity and respect towards him, his reserve, the slight disbelief in their faces as they stood in the same building where his childhood had unfolded. The polished wood, the laughter from the bar, the soft carpets. All covering years of silence. It was tender and unsettling at once.

The Shape of Home

The word home hovered between us all evening. It felt fragile, almost sarcastic in that setting: chandeliers, rich food, warm lights. For him, home had been both refuge and rejection. For her, it was a series of houses bought, repaired, sold. A movable concept that never settled. Same for me. We talked about traveling, Japan, Australia, business ideas, women’s independence, of having a daughter so far away, about how Ireland feels like a place that remembers everything. About the strange comfort of imperfection: cracks in walls, stories half-forgotten. Later that night, as the piano began again, a few of the older men gathered around it. Someone started an Irish song I couldn’t understand, and the others joined in, their voices rough and proud. I didn’t need to know the words. That’s the thing about music. It works anyway. It finds you where language stops. Watching them, standing there with such quiet dignity, I felt that small, familiar warmth of knowing you’re not completely alone in a foreign place. Just briefly, everything made sense.

Ireland’s Forgotten Children

Later, in my room, I searched for Abbeyglen’s history. The fragments I found matched the man’s story — the orphanage years, the Church oversight, the children sent away. They were part of a larger pattern that ran through much of 20th-century Ireland: industrial schools and “mother and baby homes” where poverty and moral judgment blurred into policy. The Ryan Report of 2009 later revealed the scale of neglect and abuse. Decades of discipline without compassion, of control without care.

Morning Light

At breakfast the next morning, I saw them again. He was walking slowly through the corridor. His daughter photographed him at the entrance, the castle crest above his head. There was no sentimentality in it, just a quiet goodbye. When they drove away, I stood for a while at the window, watching their car disappear down the road towards Dublin. It struck me how every journey is also a form of return, even when we don’t realise what we’re returning to. I thought about Father Horan at Knock, dreaming his airport into existence. About the man at Abbeyglen, showing his daughter a version of home that had once exiled him. About her, turning broken houses into something worth living in again. All of them, in their own way, were believers in the impossible.

Be Delusional

Maybe that’s what this trip had been about all along. The quiet audacity of belief. Belief that stories can be told without bitterness, that beauty and pain can share the same view, that memory doesn’t have to be a burden. Be delusional. It sounds reckless, but in Ireland it feels like wisdom. To be delusional is to keep going, to imagine healing where logic sees only loss.

Driving along the coast, I realised that was the real lesson of Knock’s improbable runway and Abbeyglen’s quiet ghosts: sometimes the best way to honour the past is not by escaping it, but by giving it a seat by the fire. Letting it speak, laugh, and then rest.